On April 6 of 2016, the world of professional financial advice took its first step into the future with the issuance of a Department of Labor (DoL) fiduciary rule, declaring that brokers can no longer earn commissions and other forms of conflicted advice compensation from consumers, unless they agree to do so pursuant to a Best Interests Contract (BIC) agreement with the client, which commits the advice-provider to a fiduciary standard of giving advice in the “best interests” of the client, earning “reasonable compensation”, and providing appropriate disclosure and transparency about the products and compensation involved.

Fiduciary advocates have lamented that the Department of Labor conceded several major points in its final DoL fiduciary rule, including shifting a number of key disclosures to be provided “upon request” or via the Financial Institution’s website (but not outright to the client), incorporating the Best Interests Contract into existing advisory and new account agreements (rather than as a separate fiduciary agreement), and not adopting a “restricted asset list” and instead keeping the door open to everything from controversial illiquid products like non-traded REITs, high-commission products like some variable and equity-indexed annuities, and companies that implement their own proprietary products as the “recommendation” at the end of every financial plan.

However, it appears that in reality the DoL fiduciary rule concessions were a brilliantly executed strategy of conceding to the financial services industry the exact parts that didn’t actually matter in the long run (while still reducing the risk of a legal challenge), yet keeping the key components that mattered the most: a requirement for Financial Institutions to adopt policies and procedures to mitigate material conflicts of interest and eliminate incentives that could compromise the objectivity of their advisors (or risk losing their Best Interests Contract Exemption and cause all their advisory compensation to be a Prohibited Transaction), and a second requirement that clients can no longer be forced to waive 100% of their legal rights and accept mandatory arbitration, instead stipulating that while an individual client dispute may be required to go to arbitration, consumers must retain the right to pursue a class action lawsuit against a Financial Institution that fails to honor its aggregate fiduciary obligations.

In essence, then, financial services product companies claimed that they can offer often illiquid and opaque, commission-based, and sometimes even proprietary products to consumers, while also receiving revenue-sharing agreements, and simultaneously still act in the client’s best interests as a fiduciary. And so the Department of Labor’s response became: “Fine. If and when consumers disagree, you’ll have a chance to prove it to the judge when the time comes.” In other words, while the DoL fiduciary rule didn’t outright regulate what Wall Street can and cannot do, it did change the legal standard by which all of Wall Street’s actions will be judged, and ensure that eventually the courts will have the opportunity to rule on these fiduciary conflicts. And in the long run, that will be a world of difference.

In the meantime, though, the clock is ticking for the onset of an incredibly far-reaching new fiduciary rule, and one that will impact not just broker-dealers, but RIAs as well (albeit to a lesser extent), insurance companies and annuity marketing organizations that sell variable and equity-indexed annuities, and more. The key provisions of the rule will take effect on April 10, 2017, with a transition period through January 1, 2018, by which time the last of the detailed disclosure and other policies and procedures must be put in place.

In this article, we provide an in-depth look at the keystone of the new fiduciary rule as it pertains to advisors working with individual retirement accounts: the new “Best Interests Contract Exemption”, which most broker-dealers and insurance companies will rely upon in their future attempts to provide conflicted advice to IRAs for commission compensation, and the creation of the new “Level Fee Fiduciary” safe harbor, that may (and I strongly suspect, will) eventually become the standard by which all retirement advice is delivered.

Of course, the biggest caveat is that all the new fiduciary rules apply only to retirement accounts, and not any form of taxable investment account or other investment purchased with after-tax dollars… which means the new DoL fiduciary rule will likely ultimately drive the SEC to step up on its fiduciary rule as well, as it’s clearly untenable in the long run for advice to retirement accounts to be held to a fiduciary standard, while everything else remains the domain of suitability and caveat emptor!

Michael Kitces is Head of Planning Strategy at Buckingham Strategic Wealth, which provides an evidence-based approach to private wealth management for near- and current retirees, and Buckingham Strategic Partners, a turnkey wealth management services provider supporting thousands of independent financial advisors through the scaling phase of growth.

In addition, he is a co-founder of the XY Planning Network, AdvicePay, fpPathfinder, and New Planner Recruiting, the former Practitioner Editor of the Journal of Financial Planning, the host of the Financial Advisor Success podcast, and the publisher of the popular financial planning industry blog Nerd’s Eye View through his website Kitces.com, dedicated to advancing knowledge in financial planning. In 2010, Michael was recognized with one of the FPA’s “Heart of Financial Planning” awards for his dedication and work in advancing the profession.

Read all of Michael’s articles here.

(Michael’s Note: The new Department Of Labor fiduciary rule is likely to go through several rounds of interpretations, with potential guidance updates by the DoL, in the coming months. This post will be updated as new interpretations come to light and new guidance is made available, to remain a resource on the Best Interests Contract Exemption (BICE) and the requirements for completing a Best Interests Contract (BIC) agreement with clients.)

On April 6 of 2016, the Department of Labor (DoL) issued its final “Conflict Of Interest Rule on Retirement Investment Advice”, after more than 6 years of proposals, re-proposals, and ongoing public comment periods and industry debate.

The new rule not only updates the existing fiduciary standard for employer retirement plan investment advice under ERISA from its 1975 roots (when the world of retirement planning was very different from its 401(k)- and IRA-centric reality today!), but more importantly (in the context of financial advisors) expands the scope of fiduciary duty for retirement accounts to include IRAs as well as employer retirement plans.

The essence of the new rule is the idea that when a fiduciary provides advice, it must be in the “best interests” of the client (not for the benefit of the advisor and his/her own compensation), and advisors must manage and mitigate their conflicts of interest that may taint their client-centric advice. In addition, the fiduciary rule recognized that some conflicts of interest are so severe, it is simply best to outright prohibit them altogether.

Notably, the concept of “prohibited transactions” for fiduciaries – requiring them to avoid untenable conflicts of interest – is not new. The rules pertaining to both IRAs and employer retirement plans have long prohibited a list of transactions between fiduciaries and their clients, that are viewed as being too rife with conflicts of interest to be allowed at all, including a ban on “self-dealing” transactions (where a fiduciary invests client dollars into his/her own ventures), a limitation on other forms of transactions between a fiduciary and the investment account that he/she is overseeing, and a prohibition on exercising discretion in a manner that provides the fiduciary higher compensation (e.g., shifting client investments into higher-paying investment selections).

While these rules have long been in place for employer retirement plans subject to ERISA, the Department of Labor’s new fiduciary rule extending to IRAs both the fiduciary reach, and the scope of prohibited transactions, is new territory. And doing so creates several “problems” for the existing landscape of financial advisors and brokers serving individual retirement accounts.

After all, in a fiduciary context, the receipt of a payment from a third party – i.e., a commission – would generally be a conflict of interest that is prohibited, as would revenue-sharing agreements with investment providers that can inappropriately incentivize the financial advisors to recommend some investments over others. In theory, even just the act of soliciting a client to roll money out of an existing retirement account, and into one managed by the advisor, can be a conflict of interest – albeit the most fundamental one for anyone in the “business” of being a fiduciary – given that the fiduciary advisor is not paid on the existing account but would be paid to provide fiduciary advice to the recommended new one.

Of course, in the extreme, prohibiting a fiduciary from even soliciting business as a fiduciary, because of the implicit conflict of interest, could grind all fiduciary engagements to a halt (which isn’t necessarily productive for society!). In addition, some conflicts may be minor enough in certain instances to realistically be manageable.

Accordingly, the Department of Labor has the legal ability to provide “Prohibited Transaction Exemptions” that effectively state “notwithstanding that this transaction might normally be prohibited for fiduciaries, it is in the interests of consumers for the DoL to allow it – to grant an exemption from the prohibited transaction rules – if certain requirements are met.”

And it is within this framework – that the manner in which most financial advisors engage consumers is rife with conflicts of interest that should be prohibited, except where otherwise allowed under a prohibited transaction exemption – that forms the basis of the new DoL fiduciary rule.

Under the new Department of Labor fiduciary rule, financial advisors in practice will face three core scenarios that trigger prohibited transactions, which would otherwise bar the financial advisor from engaging the client in a (conflicted) advice relationship, including where the advisor recommends:

To allow financial advisors to still engage in the above “prohibited transactions”, the Department of Labor has created a “Prohibited Transaction Exemption” (PTE) that stipulates the advisor may still engage in (and be compensated for) such recommendations.

Specifically, the new PTE is called the “Best Interests Contract Exemption” (BICE). The BICE effectively states that the fiduciary advisor must sign a “Best Interests Contract” (BIC) with the client, stipulating that the advisor will provide advice that is in the Best Interests of the client. If the advisor engages in a BIC agreement with the client, and follows its required stipulations, the otherwise-prohibited transactions – e.g., where the advisor recommends a rollover that he/she will then manage and be paid for – are now allowed.

More specifically, to gain the PTE protections of the Best Interests Contract Exemption, the Financial Institution overseeing the advisor-client relationship must:

In practice, the first two points would be captured in the Best Interests Contract (BIC) agreement with the client, while the remaining three become an obligation of the Financial Institution itself to follow (or lose its eligibility for the BICE).

Relative to the current landscape for financial advisors, there are several important points worth recognizing about how the Department of Labor has structured the requirements of the BIC agreement, and what the Financial Institution must implement to be eligible for the BICE PTE to earn conflicted compensation:

- The fact that the advisor must explicitly acknowledge fiduciary status eliminates, once and for all, the classic broker “defense” that the person who previously claimed being an advisor was still technically just operating as a salesperson and not actually acting in a fiduciary capacity. There will no longer be an opportunity for the broker to give advice to a retirement investor and then claim the fiduciary standard for advice shouldn’t apply after the fact.

- Despite all the buzz about advisors being required to act in the client’s “Best Interests”, and the debate about whether an advisor even can feasibly act perfectly in the client’s best interests at all times (does that mean we have to search the ends of the earth just to find the one product on the planet that is cheapest/best, no matter what?), the DoL rule clarifies that the real expectation is that the advisor’s advice be prudent advice (not actually the difficult-to-define “best”). Specifically, the DoL rule states that “Prudent advice is advice that is based on the investment objectives, risk tolerance, financial circumstances, and needs of the Retirement Investor, without regard to the financial or other interests of the Adviser, Financial Institution, or their Affiliates, Related Entities, or other parties.” The prudence standard draws upon ERISA Section 404, which in turn states that a fiduciary is required to act “…with the care, skill, prudence, and diligence under the circumstances then prevailing that a prudent man acting in a like capacity and familiar with such matters would use in the conduct of an enterprise of a like character with like aims.” In other words, the “best interests” standard is meant to determine whether a similar prudent professional in a similar role would have given a similar “best practices” client-centric recommendation.

- The Impartial Conduct Standards of the BICE will also require that the advisor earns “reasonable compensation”, which again is predicated not on the “lowest possible” compensation, but “reasonable” compensation. In essence, this means that the advisor does not have to be the cheapest, but simply that compensation must not be excessive based on the going market value for services rendered. Thus, similar to the “best interests” standard, the determination of reasonable compensation is based on prevailing best practices in the marketplace and a comparison to common peers, not simply an arbitrary regulator’s view on what an advisor “should” earn. Notably, such a standard is actually very accommodating of advisors providing a wide range of services, for a wide range of costs; it simply means that the costs must be commensurate to the going rate for such services. Or as DoL fiduciary Fred Reish stated it at the recent Fi360 fiduciary conference (which coincidentally got underway the day the DoL fiduciary rule was released!): “you can charge Walmart prices for Walmart service or Tiffany’s prices for Tiffany’s services, but don’t provide Walmart services for Tiffany’s prices [which would be excessive and not reasonable compensation for services rendered]!”

- The requirement to make no misleading statements may significantly increase the scrutiny on sales disclosures and illustrations, particularly for certain products that were not previously subject to such scrutiny but will be now (e.g., equity-indexed annuities, as discussed below). Of course, “sales illustrations” have long been common in the financial services industry, but it’s crucial to recognize that this isn’t just business as usual; they may be the “same” illustrations, but they will be subjected to a higher level of scrutiny, which may bring different and more harsh consequences than the past.

- The policies and procedures requirement appears to be a meaningful attempt for drive financial services institutions to change their entire culture (at least, for their subsidiaries that actually deliver financial advice). Financial Institutions will be expected to create policies and procedures that the DoL itself will review and retain jurisdiction over. If the firm does not create the proper environment by establishing mechanisms to police its own conflict of interest, the Financial Institution can lose its Prohibited Transaction Exemption under BICE, which instantly renders all of its activity a prohibited transaction breach. Firms will not want this to happen to them, and it will drive them to create a more fiduciary culture to avoid the severe ramifications of failing to do so (out of the simple self-interest preservation of what happens if they don’t).

- While some fiduciary advocates have lamented the fact that the final DoL fiduciary rule relegated many of the key disclosures to only be provided “upon request of the client” or on the advisory firm’s website (as opposed to being handed to the client directly), the depth of the disclosures is still significant. To meet the BICE requirements, the Financial Institution must disclose all “Material Conflicts of Interest”, adopt measures to prevent those conflicts of interest from causing violations of the Impartial Conduct Standards (and disclose what those measures are), and name a person responsible for addressing and monitoring this process (the Chief Conflict-Avoidance Officer!?). In essence, this means that a Financial Institution will be required to publicly announce both its Material Conflicts of Interest and its policies and procedures to handle them – which means if the process isn’t up to fiduciary snuff, the Financial Institution will effectively have handed a roadmap for a class action lawyer to sue them!

- Notably, a key aspect of the policies and procedures requirement is that Financial Institutions will be barred from having “quotas, appraisals, performance or personnel actions, bonuses, contests, special awards, differential compensation or other actions or incentives that are intended or would reasonably be expected to cause Advisers to make recommendations that are not in the Best Interest of the Retirement Investor.” This may cause a substantial reform to how many financial services institutions compensate their brokers in particular, as it potentially bars a wide range of common practices, from quota requirements to validate a sales contract, to bonuses for certain sales volumes, to incentives for selling one particular line of products over another (leading to differential compensation), etc. And the fact that the rules look not only at the compensation of the Advisor, but also the Financial Institution, its Affiliates, and Related Entities, means that even behind-the-scenes differential compensation (e.g., a wide range of common shelf-space and revenue-sharing agreements) will likely be barred under the new policies and procedures requirement. (Though notably, not all differential compensation is completely barred, as substantively different products with differential compensation can co-exist, as long as the Financial Institution can show it not inappropriately influencing advisor recommendations.)

In order for regulation to have impact, it must be enforced, including having a means for enforcement, so it’s worth recognizing how the new DoL fiduciary and BICE requirements will be overseen.

For any fiduciary advice pertaining to ERISA plans, the Department of Labor itself can continue to enforce as it has in the past, in addition to the fact that harmed participants have the right to sue in court (and in fact, ERISA-related lawsuits have had a significant impact on the employer retirement plan space in recent years).

For fiduciary advice pertaining to IRA accounts, the Department of Labor itself cannot enforce the prohibited transaction rules directly; technically, the DoL can write guidelines to define a “fiduciary” under both ERISA, and IRC Section 4975 of the Internal Revenue Code (which governs IRA accounts) under the Reorganization Plan No. 4 of 1978, but the enforcement of those rules generally falls to the IRS. And the IRS can potentially apply significant penalties - from 15% to as much as 100% of the value of the account under IRC Sections 4975(a) and (b). However, the IRS has not been active in enforcing against fiduciary prohibited transactions in retirement accounts. As a result, the Department of Labor has required those providing fiduciary investment advice recommendations to IRAs to sign the BIC… which creates the potential for the advisor (or at least, the Financial Institution) to be sued for failing to adhere to the BIC as a fiduciary, even if the IRS won’t enforce directly.

In other words, if advisors fail to follow their fiduciary obligations with respect to IRA accounts and rollovers, the DoL itself cannot enforce a proceeding against the advisor for failing to adhere to fiduciary duty, but the DoL did ensure that consumers have legal recourse by forcing Financial Institutions to leave the door open for the client’s attorney to sue instead.

In fact, extending this requirement, the BIC explicitly requires that a Financial Institution cannot require consumers to fully surrender their rights to compensation for damages or require them to fully waive their rights to pursue action in court. Instead, while the rules do allow the BIC to require that individual disputes may go to the industry-standard mandatory arbitration, consumers must retain the right to pursue a class action lawsuit in court. Which means if a Financial Institution systematically fails to adhere to appropriate fiduciary policies and procedures and implement them accordingly, the Institution faces a high likelihood of a class action lawsuit in the future, for which the required disclosures will provide a roadmap to the plaintiff’s attorney to pursue!

In addition, the Department of Labor still retains the right to evaluate a Financial Institution’s policies and procedures themselves, and has already vowed that it will be “closely monitoring” Financial Institutions as they roll out their new policies and procedures in the coming year. If the policies and procedures themselves are not up to snuff, the Department of Labor can potentially declare that the Financial Institution has failed to meet the BICE requirements – which would render the firm ineligible for the necessary Prohibited Transaction Exemption, causing all of its advisors and conflicted compensation to be in violation of DoL rules, a potentially catastrophic outcome that Financial Institutions will desperately wish to avoid!

In the world of fiduciary advice, it has long been recognized that earning level compensation which does not vary by the product being recommended (e.g., ongoing level AUM fees, rather than upfront commissions) is an effective way to mitigate many conflicts of interest. In fact, the Pension Protect Act included a level-fee prohibited transaction exemption to help facilitate otherwise-conflicted advice in employer retirement plans a decade ago.

Along these lines, the final DoL fiduciary rule includes an alternative (and “streamlined”) way for advisors who receive level fees to qualify for the Best Interests Contract Exemption, without actually being required to complete a full Best Interests Contract, by instead qualifying as a “Level Fee Fiduciary”.

The “Level Fee Fiduciary” (LFF), and the idea of providing an easier exemption for those who were already fiduciaries that were simply shifting clients from one form of level compensation to another, was a concept put forth in Comment letters to the 2015 version of the fiduciary rule proposal, most notably and thoroughly by the American Retirement Association (though also supported by the Financial Planning Coalition comment letter as well).

In the final rule, the “Level Fee Fiduciary” qualifies as such “if the only fee or compensation received is a ‘Level Fee’ that is disclosed in advance to the Retirement Investor.” The DoL states that such levels fees could be either calculated as a (level) percentage of AUM, or as a set fee that doesn’t vary at all with the particular investment (e.g., a retainer fee).

Notably, to be eligible as a “Level Fee Fiduciary”, the advisor would not need to already be an RIA receiving level AUM fees. It could be a broker who receives level fees via 12(b)-1 fees, or as compensation for a fee-based wrap account. However, to be eligible for the Level Fee Fiduciary exception, the advisor – and the Financial Institution, and its Related Parties and Affiliates – must receive only that Level Fee, and not any other commissions or transaction-related compensation. Thus, adding 12(b)-1 fees on top of level fee compensation would be problematic, as would other types of revenue-sharing agreements (disqualifying the engagement from eligibility for the Level Fee Fiduciary exemption, and forcing the firm to follow and rely upon the whole Best Interests Contract instead).

For advisors and their Financial Institutions that do qualify for the LFF exception, the firm is still required to provide a written statement of fiduciary status (which could be part of the client agreement), must still comply with the required standards of impartial conduct, and must still document the specific reason and validation for doing the rollover transaction and that it was in the interests of the client (e.g., document both the costs of the plan, the new costs of the advisor and his/her chosen investments in the IRA, differences in the level of services [such as whether it is investment-only or includes financial planning advice as well], etc.).

If these requirements are met, though, the firm does not have to comply with the full scope of completing the BIC agreement and the full extent of the policies and procedures disclosure requirements for the Financial Institution (since, presumably, there would be less in the way of material conflicts of interest to disclose for the Level Fee Fiduciary in the first place).

In the long run, it’s entirely possible (and I think, likely!) that most/all advisors will end out pursuing the path of being a Level Fee Fiduciary, to avoid both the BIC agreement obligation and the associated policies and procedures requirements. In other words, similar the rules for RIAs that have custody, an investment adviser can have custody of client assets, but is subjected to significant additional scrutiny by doing so, such that in practice most RIAs simply avoid custody altogether to avoid the additional custody compliance requirements. The Level Fee Fiduciary safe harbor will likely have a similar impact over time.

In what was viewed as a significant concession to the industry, the actual execution of the BIC agreement itself (for those who provide fiduciary investment advice and are not Level Fee Fiduciaries) was greatly expedited in the final rule.

While the prior proposal of the rule would have required the BIC to be a separate written contract, that the advisor would have had to deliver and get signed before even talking to a prospect about something that could have been deemed “advice” or a “recommendation”, the final version of the rule stipulates that the BIC doesn’t have to be signed until the client actually opens an account. In addition, the BIC can be incorporated directly into the paperwork of a client advisory agreement or account opening document, rather than as a standalone separate contract to sign.

Notably, the final rule also stipulates that the BIC will generally be a contract between the client and the Financial Institution (not “just” the advisor). To some extent, this was done to accommodate firms that have multiple advisors serving a single client, so that a new BIC doesn’t have to be signed each time a new/different advisor interacts with a client (which would have created issues for everything from when a new advisor takes over the clients of a prior advisor, to “call center” firms that may have multiple advisors who respond to a client inquiry).

Notwithstanding the timing of when the BIC will be signed, though, and that multiple advisors may have interacted with the client along the way, the final rule also requires that all recommendations of the fiduciary advisor are subject to the BIC, retroactively including the recommendations that were made to the client leading up to the transaction for which the BIC was ultimately signed. Thus, even though the BIC won’t be signed until the implementation phase with the client, it will still cover all the advice recommendations leading up to that recommendation being implemented.

Given that many advisors will be transitioning into fiduciary status for the first time – and thus becoming subject to the prohibited transaction rules and the requirement to obtain a prohibited transaction exemption by following the BICE requirements – the DoL provided several “grandfathering” provisions to provide relief transition for those who have a large base of existing commission payments coming in.

First and foremost, the final DoL fiduciary rule outright grandfathers any ongoing commission payments that continue to be received for advice that was provided prior to the effective date of the new rules (which will take effect in 2017, as discussed below). Thus, brokers will not be required to give up existing 12(b)-1 fees and other trailing commission payments.

In addition, any ongoing client contributions that were already committed to as part of a systematic plan will also be permitted to continue (even if it triggers new/ongoing commissions), without being newly subjected to the BIC requirement.

However, any new recommendations to an existing client, including a recommendation to make new additions to existing commission-based investments (that would trigger a new commission or other additional compensation to the advisor), will require a new BIC agreement once the new rules take effect. In addition, existing clients will ultimately need to be transitioned into the BICE exemption once the new rules take effect, which can be done with a “negative consent” procedure (sending a letter to clients informing them of the new agreement and giving them the option to leave if they don’t want the new arrangement for some reason, but otherwise defaulting them into the new fiduciary engagement).

And of course, any new clients and new advice after the applicability date (discussed below) will be subject to the new BICE obligations.

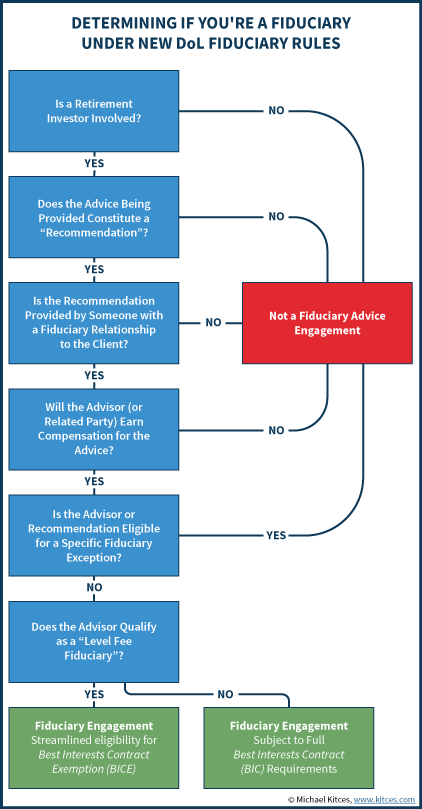

One extremely important aspect to the new BICE requirements to act in the best interests of a client as a fiduciary is to know when the advisor actually has a fiduciary obligation to the client – a threshold which is critically important to define in the first place.

First and foremost, it’s important to recognize that the fiduciary obligation under the final DoL rule, and the related BICE compliance requirements, only apply in the case of advice provided to “Retirement Investors”, which is defined as participants and beneficiaries of an ERISA plan, IRA owners, and those who are acting as fiduciaries for an IRA or ERISA plan (e.g., plan sponsors).

Thus, advice outside the scope of a retirement account – whether pertaining to an individual brokerage account, a bank account, or non-investment-account alternatives purchased with non-qualified dollars (from a non-qualified annuity to a direct-purchase non-traded REIT) – is not subject to the new rules. Notably, though, the DoL acknowledges that a Health Savings Account (HSA), Medical Savings Account (MSA), and Coverdell Education Savings Account (the so-called “Education IRA”) would be subject to the new fiduciary rules (as they’re part of the same prohibited transaction requirements under IRC Section 4975(e)(1) that apply to IRAs as well).

If a Retirement Investor is involved, the next question is whether “Investment Advice” is being provided. Investment advice is defined as advice for which the advisor receives a fee or other compensation (directly or indirectly) for providing a recommendation on either:

- The advisability of acquiring, holding, disposing of, or exchanging, securities or other investment property, or a recommendation as to how securities or other investment property should be invested after the securities or other investment property are rolled over, transferred, or distributed from the plan or IRA; or

- The management of securities or other investment property, including, among other things, recommendations on investment policies or strategies, portfolio composition, selection of other persons to provide investment advice or investment management services, selection of investment account arrangements (e.g., brokerage versus advisory); or recommendations with respect to rollovers, transfers, or distributions from a plan or IRA, including whether, in what amount, in what form, and to what destination such a rollover, transfer, or distribution should be made.

If Investment Advice is being provided, the next question is whether the advice is being delivered by someone who would be expected to have a fiduciary advice relationship with the client, which means a person who:

- Represents or acknowledges that it is acting as a fiduciary;

- Renders the advice pursuant to a written or verbal agreement, arrangement, or understanding that the advice is based on the particular investment needs of the advice recipient; or

- Directs the advice to a specific advice recipient or recipients regarding the advisability of a particular investment or management decision with respect to securities or other investment property of the plan or IRA.

Notably, in the context of determining whether a fiduciary advice relationship exists, a key question is whether the discussion with the client actually constitutes a “recommendation”. Accordingly, a recommendation itself is defined as:

- For purposes of this section [of the DoL fiduciary rule], “recommendation” means a communication that, based on its content, context, and presentation, would reasonably be viewed as a suggestion that the advice recipient engage in or refrain from taking a particular course of action. The determination of whether a “recommendation” has been made is an objective rather than subjective inquiry. In addition, the more individually tailored the communication is to a specific advice recipient or recipients about, for example, a security, investment property, or investment strategy, the more likely the communication will be viewed as a recommendation. Providing a selective list of securities to a particular advice recipient as appropriate for that investor would be a recommendation as to the advisability of acquiring securities even if no recommendation is made with respect to any one security. Furthermore, a series of actions, directly or indirectly (e.g., through or together with any affiliate), that may not constitute a recommendation when viewed individually may amount to a recommendation when considered in the aggregate. It also makes no difference whether the communication was initiated by a person or a computer software program.

Notwithstanding these requirements, the rule also specifically acknowledges certain scenarios where something is clearly not a recommendation, and/or where something would be deemed a recommendation but is not fiduciary advice anyway. These scenarios include:

- Just making a platform of investment options available to participants is not deemed advice (as long as it’s just being offered openly without regard to the individual needs of the specific investors);

- General communications

- Investment education

- General financial, investment, or retirement information

- Certain generic asset allocation models to provide guidance but not specific participant advice

- Interactive investment materials such as questionnaires or worksheets that are simply meant to help people evaluate their options (but not steer towards any one in particular)

While the DoL fiduciary rule provides significant guidance already regarding these various definitions and exceptions, expect the Department of Labor to issue additional regulations and guidance in the coming year to further clarify areas of ambiguity about where the lines are drawn regarding the exact moment at which a fiduciary engagement applies.

One notable distinction to the new DoL fiduciary rules is that their applicability is based on whether advice is provided to a Retirement Investor (i.e., pertaining to a retirement account), and not based on what type of product it is.

Thus, while historically, the sale of securities products was regulated by FINRA, the sale of insurance products is subject to state insurance regulators, and investment advice was regulated by the SEC (or state securities regulators), the DoL fiduciary rules cut across all of these product silos to provide a fiduciary obligation for recommendations pertaining to retirement accounts, regardless of which of these product types are implemented.

As a result, the new requirements will apply to anyone who provides a recommendation about whether to rollover an IRA, or about how those IRA assets should be invested. This means that all the fiduciary requirements, including the disclosure provisions and the requirements about appropriate illustrations that are not misleading, will apply not just to “traditional” investment products, but also annuity products sold within retirement accounts – specifically, variable annuities and equity-indexed annuities, which the Department of Labor notes are “complex” enough to merit such scrutiny and be subjected to the BICE requirements (which means insurance agents selling annuities into retirement accounts will be treated as fiduciaries for the first time ever, so no more inappropriate claims of “no-cost” equity-indexed annuities that are paying big commissions under the table!).

Fixed-rate annuities, however, will be eligible for a less stringent (but also updated) Prohibited Transaction Exemption 84-24, and not need to comply with the full BICE obligations.

Under the final version of the Department of Labor Conflict of Interest Rule, the rule will become “effective” 60 days after it is entered into the Federal Register, but actual enforcement of the new rules will be delayed to allow the industry time to adapt. Instead, the “Applicability Date” for the IRA rollover and other DoL fiduciary rules will be April 10, 2017.

Even as of the April 10, 2017 applicability date, advisors who give fiduciary investment advice to Retirement Investors will be subject to the fiduciary obligation, but the detailed policies and procedures and related requirements of the BICE obligation (and enforcement for failing to implement those requirements) will be delayed until January 1, 2018 to allow the industry a “transition period” of adjustment.

In practice, this means that advisory firms of all types have a year to figure out when/whether they are providing fiduciary investment advice to Retirement Investors (i.e., when the fiduciary rule applies), and to make adjustments to their compensation and systems to ensure that their subsequent actions are meeting the fiduciary requirements. This also provides time for firms to either affirm that they meet the requirements to be a Level Fee Fiduciary, or adjust their practices so that they can qualify as a Level Fee Fiduciary when the time comes. (Notably, this may disrupt some relatively “common” but already controversial practices of RIAs today, such as charging different levels of AUM fees for bonds versus stocks, which under the new rules would disqualify the firm from being a Level Fee Fiduciary, and possibly be ineligible for the BICE altogether, due to the conflicted compensation.)

Over the subsequent months, Financial Institutions will need to complete the implementation of their policies and procedures, and their supporting Best Interests Contract (BIC) agreements themselves, and transition ongoing advice clients into the new agreements (through the DoL’s prescribed “negative consent” default-in process).

Advisory firms should also recognize that whether they must complete the BIC agreement, or operate as a Level Fee Fiduciary, they will need to adopt a new level of scrutiny and review to substantiate any rollover recommendation they make (along with any recommendations to transition from a commission-based account to a fee-based account) after the April 10, 2017, applicability date. This is a new level of documentation that most advisory firms are not accustomed to, and while most may simply find this a minor paperwork speedbump, in some cases it may force firms to really evaluate whether their advice and value-add is sufficient to truly justify a recommendation to roll over retirement assets from an existing 401(k) plan.

In the meantime, arguably the greatest adjustment pressure will be on insurance and annuity companies, and broker-dealer firms, that will not likely qualify for the Level Fee Fiduciary exception and thus must not only engage in a Best Interests Contract (BIC) agreement with clients, but institute the new requirement for policies and procedures to both disclose and then manage and minimize any conflicts of interest. In the long run, this will arguably be the largest adjustment to the fiduciary rule, impacting not merely the brokers and insurance agents at the firm – including potentially how they’re compensated, as differential compensation and sales incentives are eliminated – but the processes and procedures and even business model and structure of broker dealers and insurance companies themselves. Not because the Department of Labor mandated which types of compensation or products can stay or go, but simply because the firms will now be cognizant that if they cannot defend their processes and procedures to the DoL – and the outcomes to a court in a future class action lawsuit – that failure to effectively comply with the new fiduciary rule could mean a fiduciary breach that could damage or put the firm out of business altogether.

Ultimately, the interpretations of the new DoL fiduciary rule will likely continue for months, and given the delayed Applicability Date and the subsequent Transition Period, it will potentially be years before the full impact of the new rules are felt.

Nonetheless, my gut having read the entire 1,000+ pages of the rule and its supporting materials, is that the Department of Labor was quite savvy in picking exactly which parts of the rule they conceded, and which remained intact.

Because a detailed look reveals that as long as the core of the rule remains intact – that Financial Institutions must disclose all of their compensation and Material Conflicts of Interest, that advisors must affirm their fiduciary duty, and that Financial Institutions that offer conflicted advice must forever leave the door open to a future Class Action lawsuit – most of the points that the DoL conceded weren’t exactly much of a concession at all.

In other words, fiduciary critics have lamented that the final DoL rule reduced the depth of up-front disclosures, allowed the BIC to simply be incorporated into advisory and new account agreements, and eliminated the restricted asset list (opening the door to both controversial illiquid products like non-traded REITs, high-commission products like some variable and equity-indexed annuities, and proprietary products). But as long as the core fiduciary rule and its enforcement remain intact, these concessions may not have been concessions at all. It simply means that instead of regulating against those products and scenarios in the first place, the DoL will force the issue into the courts through class action lawsuits, and let future judges sort out what really works and what doesn’t!

In point of fact, this is arguably the whole point of principles-based fiduciary regulation – not to prescribe a never-ending series of ‘precisely’ written regulatory rules, which just invite industry participants to push to the very limits of the line without putting a toe over – and instead creates the kind of principles-based guidance with a level of ambiguity that forces firms to shift their culture, for fear of being found guilty after the fact (coupled with the outright banning of some problematic behaviors, such as eliminating sales contests, and forcing others like under-the-table revenue sharing agreements into the light of day).

In essence, the Department of Labor has collectively said to the financial services industry “You claim that you can still offer illiquid, commission-based, proprietary products to consumers while also receiving revenue-sharing agreements, and simultaneous still act in the client’s best interests as a fiduciary? Fine. You can prove it to the judge when the time comes.”

I suppose when the time comes in a few years, we’ll see what happens. Though I suspect that many Financial Institutions, when faced with the possibility of losing a very expensive and high-profile class action lawsuit, will feel compelled to take it upon themselves and reform their own business practices, to avoid the risk of putting themselves out of business. Or alternatively, may simply decide it’s easier to switch over and become a Level Fee Fiduciary, because there’s less ambiguity and legal danger to executing the simpler and less conflicted business model. Which perhaps is exactly what the very smart folks at the Department of Labor wanted to see happen in the first place.

In the meantime, though, it seems likely that the Department of Labor’s actions will ultimately force the SEC to act as well, as we now have what seems to be an untenable conflict where an investor’s retirement account is subject to a higher standard and a greater level of scrutiny than his/her brokerage account and other non-qualified assets. On the plus side, by the time the SEC gets around to acting, the DoL rule may already be fully implemented and in force, in which case the SEC will get the political cover it needs to finally step up its own rules, if only to “conform” to the Department of Labor. Which means by sometime around 2019 or 2020, we may finally have a fiduciary standard for all investment advice!

So what do you think? Did the Department of Labor do a “good job” with its new fiduciary rule? Did it go too far, or not far enough? Are you concerned about your ability to comply with the new rule? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!